The most famous surviving examples of this technique are the embroideries of St. John the Baptist which are now preserved in the Museo dell’Opera del Duomo in Florence. They are a series of 27 scenes of the life of St. John the Baptist which once decorated vestments worn by the priests of the Baptistry commissioned by the members of the Arte di Calimala.

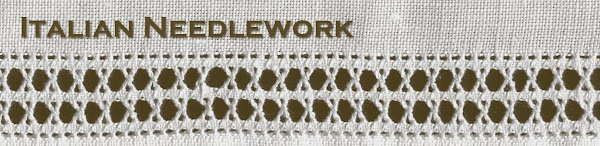

I'm sorry my photo is not very clear, but here is one of the pieces:

Painter and Architect Giorgio Vasari mentions in his book “The Lives of the Most Eminent Painters, Sculptors and Architects” (first published in Florence in 1550) that the artists who designed for needlework had the ambition to produce embroideries which looked as much like paintings as possible.

In 1437 Cennino Cennini of Florence wrote out techniques for artists who were commissioned to design for embroidery (Il Libro dell'Arte). It was the artist, not the embroiderer, who drew out the designs on the ground fabric, and there were precise instructions for designs on linen and different ones for designs on velvet.

Goldwork embroidery on clothing and furnishings may not have been a luxury for the average citizen but nothing, not even Sumptuary Laws restricted the rich. In Old Italian Lace, Elisa Ricci quotes an inventory document which states: "In the wedding-trousseau of Elisabetta Gonzaga of Montefeltro (1488) the cushions were of crimson satin with a network of gold and silver, two shirts, one of cambric, the other of bombasine were worked with gold; the sheets were trimmed with gold and gold fringe." And again here she quotes inventory documentation of the wardrobe of Lucrezia Borgia, dated 1502: "minute descriptions are given one after another of embroideries for bed-furniture in silk and gold, velvet embossed with gold, and two cushions of green velvet with tassels and lace of gold."

The Church was often the commissioner of expensive needlework. A Renaissance period dalmatic, credited to the region of Umbria is preserved at the Orvieto Museo del Duomo. It is a rich red brocaded velvet which has the scenes of the “Adoration of the Magi”, the “Presentation in the Temple”, and the “Resurrection and Ascension” embroidered in gold and silk threads on it. It belongs to a set of another dalmatic and a chasuble, the designs of which are credited to either the artists Luca Signorelli, Sandro Botticelli or Raffaellino del Garbo.

Check out this Italian Corporal Cover at the Victoria & Albert museum.

While religious material provided endless subject matter for gold embroideries, hunting scenes were popular as well. The nuns of Florence were also doing commissions of embroideries at this time. Their skill was praised by the Bishop of Florence and by Fra Savonarola who then later in the century changed his mind and reproached the sisters for devoting their time to the "vain fabrication" of gold laces with which to adorn the houses and persons of the rich.

The 16th century was the height of decorative design and it is at this time that Italian styles and fashions had the greatest influence on Europe. During this period ancient Roman houses were being excavated and an interest in classical design began to be reflected in art. "Since the excavated houses of ancient Rome, by now buried under the detrius of years, emerged as caves, they became known as grottoes and their wall paintings were described as grotteschi, or grotesques. Essentially the style consisted of a light, cool balanced scheme of cartouches set in an airy framework of linear and floral decoration, which was whimsically or even ludicrously interspersed with imaginary beasts, mask and human or anthropoid figures" (Needlework, an Illustrated History, 1978). The artist Raphael is credited with developing this type of design work.

An example of Raphael grotesque design:

Around the same time, Islamic decoration was also used by Renaissance designers and these two design influences were combined to create the style of Renaissance artwork. Early Middle Eastern design inherited through Sicily and flower patterns were also incorporated. Classical acanthus leaves, arabesque scrolling or wave patterns sometimes combined with animal patterns were stylized to geometric ground-covering patterns.

Symbolism and double meaning was popular among the people of Italy in the 16th century and was often reflected in Goldwork embroidery along with heraldry, monograms and ciphers. These types of patterns were used for wall hangings, bed valences, covers for chests and tables, horse trappings and coverlets worked in gold threads usually on velvet or satin or in appliqué outlined with applied braids.

Catherine de’Medici of Florence was a great patron of embroidery and was a highly skilled embroideress herself, having learned the art while in the convents of Florence during her early childhood. It is said that Catherine took the most skilled of Italian embroidery craftsmen with her to the French Court and while there, spread Italian needlework techniques among the French. I love this quote from an essay in a 1930 issue of Antiques Digest: "Catherine de’Medici, always interesting and intriguing because of the times she reflected, presents a magnificent picture of the luxury of woe. On the death of Henri II she tore down the gorgeous brocades of the bed and replaced them with more of magnificence than even color could express. Into this bed they popped the widowed queen, and this is how it was draped. A canopy was over her head of black silk damask lined with white. From this depended a dossier which hung behind the bed’s head, also of black damask, but embroidered in silver. But the fine effect was given by the curtains long and full, all of black velvet. They were embroidered with gold and silver and finished across the hem with silver fringe. When they parted it was to reveal the queen lying under a coverlid of black velvet and black damask set off with flashes of silver and pearls. Who could doubt the sincerity of woe thus beautifully expressed? This style of bed was aptly called the lit de parade."

The Metropolitan Museum of Art in New York has a late 16th century, possibly Venetian, woman’s camicia with lavender silk and gold embroidery patterns. Unfortunately, their website does not have a photo of this piece and they have no record of who it belonged to.

Check out this amazing Italian christening blanket at the Victoria & Albert museum! Don't forget to click on the "More Information" tab to read all the information.

In another post we will explore Italian Goldwork in other time periods.

My best compliments for your accurate work. As sometimes happens, you can find better blogs of italian features out of Italy. I like really much your cultural approach: I will follow you.

ReplyDeleteThank you for adding my blog in your list!

Elisabetta by elisabettaricami

Thank you Elisabetta! I am enjoying your blog too!

ReplyDeleteMetal Threadwork in Italy was my thesis for a Goldwork course I took some years ago... it took me six months of research to write it. Six years later most of the links are out of date and unusable! I had to do a little updating for this chapter and I imagine I will have to do the same for the other chapters before posting them. It keeps me learning!